Changing Tides: A History of Bellingham\'s Waterfront

Story and video by Brinnon Kummer, Jessica Vangel and Roisin Cowan-Kuist

When one thinks of Bellingham, what comes to mind? Is it the beautiful natural setting, tucked between the Salish Sea and the rolling greenery of the Chuckanut Mountains? Is it the vibrant social scene, with a microbrewery or coffee shop on every other block and little boutiques filling the gaps in between? Maybe it’s the history, the colorful personalities of its residents, the recreational opportunities, the resident deers, etc. Whatever it be, the city of subdued excitement seems to have a little something for anyone who ventures far enough north to reach it.

Despite being planted along the shores of the sea, Bellingham’s downtown waterfront rarely finds itself on the cover of tourist brochures. Haunted by the rusted ghosts of industries past, for many decades the area had little to offer to the average visitor except for its rich history. A history that put Bellingham on the map and pumped blood into its concrete veins.

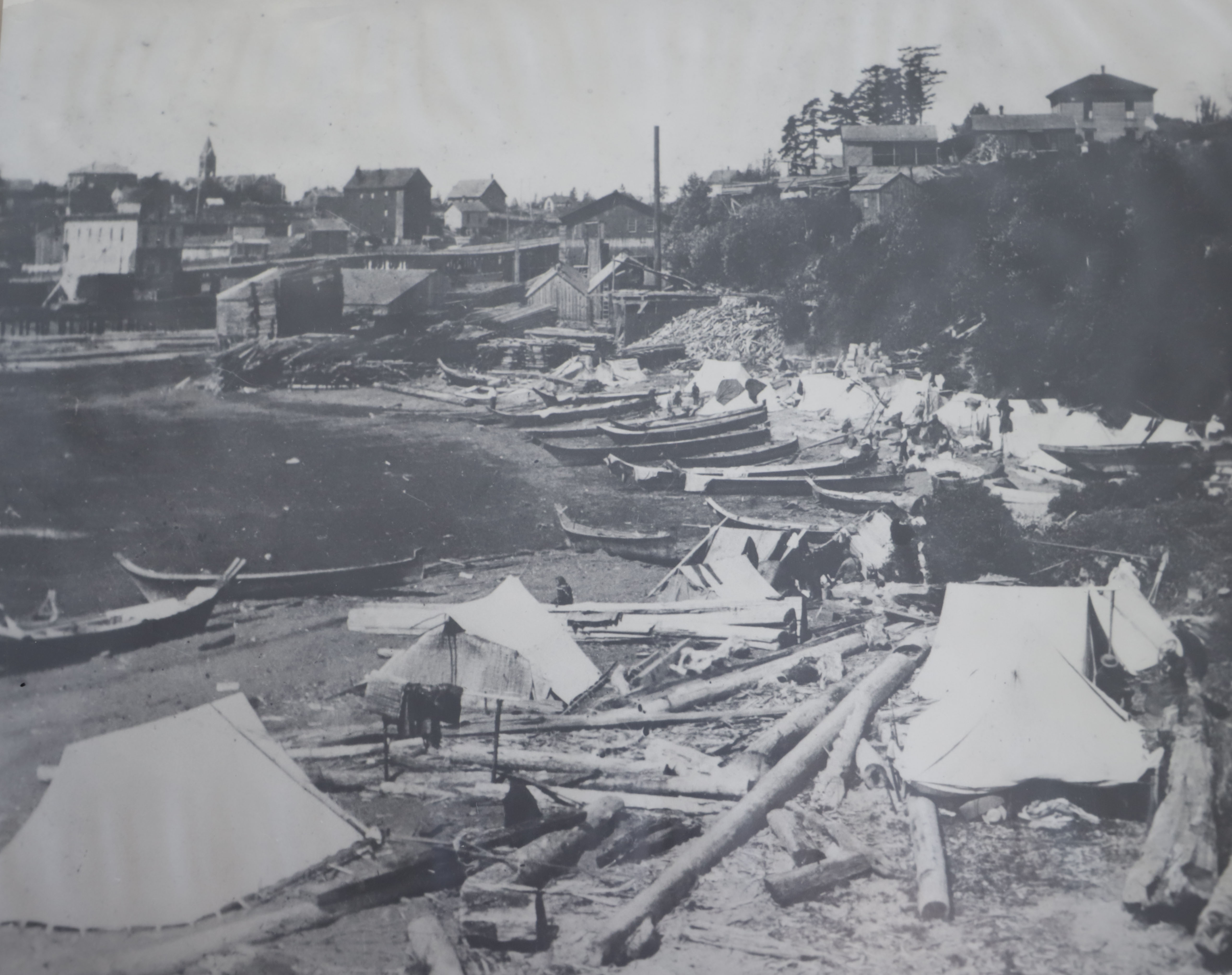

The area was, like the rest of the country, first inhabited by native tribes. In Bellingham, it was primarily occupied by the Lummi tribes, who survived off the wealth of aquatic life and innovated a number of fishing techniques that are still used today. In 1852, Captain Henry Roeder of Ohio and Russell Peabody of San Francisco came to Olympia looking for a waterfall powerful enough to build a mill on, hoping to produce the lumber to rebuild San Francisco after its great fire. With the help of Lummi Chief Chow’it’sut, they found just that at Whatcom Falls. Though they were late to rebuilding San Francisco, the lumber created here would be used to instead build Victoria, British Columbia to the north.

With more and more people beginning to settle in the area, it was only a matter of time before the vices and guilty pleasures of humanity began to find their place as well. Down by the tideflats in Old Town is where many of the saloons and brothels were clustered, with literal red string lights hung up so there would be no mistake where you were. The hope was that labeling the area would help to contain it all to that one part of town. That worked well, until 1910, when women in Washington gained the right to vote, and prostitution was voted out of Bellingham, with alcohol following close behind. This, as is well known, didn’t stop either of the two practices, but instead distributed them across town, hidden in secret establishments.

The boom of the late 1800’s meant that more infrastructure needed to be built to accommodate the new residents. Eventually they ran out of room on land, so they began to build piers, and hotels and business were built on tall beams out over the water, as deep as was possible at the time. Then, in 1904, a relatively new invention offered new prospects for the city, the dredging machine. Over the next decade, much of the current old town area was dredged, dragging dirt and sediment from the bottom of the sea up towards the shore where it could be compacted and made into sturdy land that could support much larger buildings.

With the invention of steam power and the newly dredged land, mills could now move away from streams and falls to be closer to the timber or closer to the sea, where shipment by boat was dominant until the railways were built. Along with lumber and paper mills, in 1900, salmon canneries and other fisheries sprung up along the waterfront as companies learned how to can and properly preserve fish for shipment. These mills and canneries brought in a number of immigrant workers from Asia and Europe alike, which led to several incidents of protest and riots among locals, culminating in the East Asian population being ran out of town by a white mob.

The industries boomed and houses and businesses alike sprung up throughout the city, until the stocks of timber and salmon were depleted and the mills and the jobs they carried with them began to die off in the mid 20th-century. For decades after, these mills would sit, crumbling and decaying, until initiatives were made to restore the area to something other than an industrial graveyard.

New parks were built, such as Waypoint Park with old structures such as the “Acid Ball” from one of the mills being made into a sculpture. The Bellwether area came about after the old mill was torn down, the area was dredged and after ten years of letting the sediment settle, businesses began to be built. Now, the city looks to remove the last of the paper mills and plants, and continue paving the way for new businesses and recreational opportunities to prosper. The trouble comes with how to do this in a way that does the least damage to the area’s ecosystem, which has delayed the developments for some time.

It’s hard to say what Bellingham will look like in one hundred, twenty, or even ten years, but it can be certain that some things will not change. The city will always boast its natural charm and unique character. There will always be stories to be told, and new ones to be written. The waterfront that has given the city so much will continue to develop, and offer new avenues of social and economic opportunity. Only time will tell what subdued excitements are waiting to be unearthed.